Bronica: How a Japanese Rice Farmer Tried To Give Hasselblad a Run for Its Money

![]()

Hasselblad needs no introduction. Ever since the launch of its 500C, the boxy, modular medium-format waist-level SLR has defined the output of genres ranging from street to fashion photography throughout the mid-20th century and beyond.

Case in point, take a look at Bronica. You might not have heard of Bronica before, let alone the cameras it created between the 1960s and the 2000s. For much of that time period, however, Bronica was as much a major player in the medium-format field as Hasselblad themselves – and plenty would argue that the former had the edge in some important metrics.

Was that truly the case? Could Japanese charm and craftsmanship triumph over Swedish innovation and design? And where did Bronica go, while Hasselblad remains a fixture in the world of digital medium-format photography today?

There’s no better way to find that out than by a dive into the past.

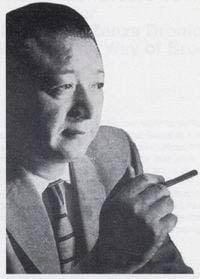

Zenzaburo Yoshino, an Innovator of Unlikely Origins

The story of Bronica begins with a man named Zenzaburo Yoshino.

The third-generation heir to a family-owned rice farm, Yoshino grew up in the Taisho-era Japanese countryside not far from Tokyo. Though moderately successful, the family business hit hard times during Yoshino’s early adulthood, as wartime rationing and later the American occupation threatened to kill off the traditional way of life for his family.

Like many others, Zenzaburo decided to diversify into bold, new ventures that were gaining in popularity at the time in post-imperial Japan. Right away, he had his eyes set on only one thing: building a camera. An unorthodox choice in the postwar Japanese economy for sure, but Yoshino had been fascinated since an early age with camera mechanisms and design, especially pre-war German jewels like the Leica and the Rolleiflex.

There was just one problem. Neither Yoshino himself nor his family or any of his friends and partners had the budget to justify the expense of designing and building a camera from scratch.

Thus, Yoshino decided on a long-term business strategy where he would concentrate on building a brand reputation on profitable luxury goods to then use as a springboard to later enter the photographic field.

Exactly that is what would happen over the coming years. With funds gained from a successful stint as a Tokyo-based used camera salesman, importing the very cameras he had lusted over in his youth, Yoshino launched his own venture, the Shinkodo Works, in 1947.

As he had anticipated, Yoshino found that no amount of buying and re-selling old cameras could give him the budget nor the time needed to develop his own from scratch. Hence, Shinkodo focused on entirely different luxury products for the Japanese market – cigarette lighters, jewelry, and even beauty cases.

These expensive items were especially popular with the American occupation troops, who had a lot more disposable income to spend than the average Japanese. To take advantage of that fact, Shinkodo increasingly employed advanced craftsmanship and luxurious Art Deco-style designs, which were a real hit among its target audience.

Soon enough, more product lines would emerge – mechanical watches, bags, and all sorts of fashionable accessories. With the growing success of Shinkodo, Zenzaburo Yoshino was able to position their products as top-shelf items in some of Japan’s biggest department stores.

Transforming Bronica Into a Cameramaker

To build a recognizable brand name for his future plans, Yoshino settled on a peculiar title: Bronica, stemming from “Buroni” (Brownie, as in the Kodak Brownie), which is what 120 medium-format film was known as in Japan back then. The ‘ca’ was added as a little reference to contemporary brands that used “camera” in their official names, such as Leica, Konica, Fujica, and others.

This name alone signified that, by the turn of the 50s, Yoshino felt ready to start thinking more seriously about the passion that launched his entrepreneurial endeavor: making his own camera.

Of course, while Shinkodo had access to a fair number of talented artisans and craftspeople, neither Yoshino nor any of his partners were camera designers by trade. They also lacked any experience in optics – crucial for the success of any camera system, no matter how sound from a mechanical perspective.

Yoshino chose to circumvent the latter problem by partnering with another Japanese company to produce lenses for his future camera system. Before that could happen though, Bronica needed to have a machine to present to the public and the commercial press first.

The official go-ahead for the project to design Bronica’s first camera came from company management in 1952.

The Original Zenza Bronica Camera

Yoshino based a lot of the design principles that went into the first Bronica – named the Bronica Z after Zenza himself – on the various sketches and ideas he’d collected over the years.

The integral core principles he decided on first were that the camera would shoot on 120-format “Brownie” roll film, feature a modular design including interchangeable lenses and backs, and be small and portable.

Initially, Yoshino had no plans of directly competing with any major players in the medium-format camera industry. However, as the 50s passed by and the development of the Zenza Bronica dragged on, he soon realized that the bulk of the market for a compact, medium-format SLR was coalescing around just one brand name: Hasselblad.

Before it was even finished, the mission statement of the Zenza became to serve as a Japanese answer to the still-fresh Swedish sales hit.

Releasing the Zenza

Before the first customers got to handle their Zenzas, Yoshino went on a grand marketing tour. To promote his new camera, “Mr. Zenza” came to the United States and helped publish an exclusive preview of the Bronica with Burt Keppler, the legendary publisher and columnist for Modern Photography.

Yoshino rightly assumed that with the recent success of Japanese brands like Nikon and Pentax overseas, marketing the Bronica to North American buyers was an essential element to its future success. Showing off a prototype at the prestigious Philadelphia Camera Show in 1959, he all but guaranteed that all eyes were on Bronica in the Western hemisphere.

The marketing campaign was an unprecedented one for such a small, foreign business with literally zero name recognition in the world of photography. Lots of promises made by Yoshino about his prototype stunned the press and confounded commentators.

This included, for example, an instant-return mirror and automatic aperture stop-down – something that was considered a standard feature on high-end 35mm SLRs at the time, but had yet to make the jump to the mechanically different medium-format SLR design.

The Zenza was also said to feature a high-speed focal-plane shutter going up to 1/1250th of a second, again setting a record for medium-format cameras in its class.

The original Zenza Bronica saw its initial public release later that year. That’s hot on the heels of the standard-setting Hasselblad 500C of 1957, the brand’s best-selling model yet.

Bronica never lied about its world-class features, and they would indeed make it into the final product. But how could a first-time camera from a relatively unknown brand do such a thing?

The Zenza Bronica’s Innovative Design

Much of it had to do with the Bronica’s exotic shutter. Zenzaburo Yoshino, while not a professional engineer, knew a lot about camera mechanics thanks to his avid passion for collecting, shooting, and tinkering with a variety of models since his early days. He also knew about the limitations of Hasselblad’s original design and wished to improve on it significantly.

In doing so, Yoshino created an unorthodox focal-plane shutter that ran vertically, coupled to a swinging reflex mirror mounted in reverse – that is, flipping down instead of flipping up like on most cameras.

This had two prime advantages. First, longevity and high-speed reliability, the very same issues that prompted Viktor Hasselblad to abandon focal-plane shutters on his own camera, were greatly improved. Second, the Zenza could easily accommodate retrofocus lenses that needed a great deal of space within the camera body. That reduced future development costs for the Zenza’s all-new lens mount.

Speaking of which, Bronica’s lenses were outsourced to a major Japanese optical manufacturer, just as Yoshino had planned from the beginning. In the end, Nippon Kogaku was chosen as Bronica’s official partner – that’s right, none other than Nikon!

“Nikkor lenses are standard for the Bronica,” the original owner’s manual states. “No finer optics could be found whose quality more suitably complemented the superb performance of the Bronica.

“Nikkor lenses have proved to be the finest in 35mm photography field, a field in which optical quality is especially critical and demanding. Available focal lengths range from 50mm wide angle to 1000mm super telephoto. The 50, 75, and 135mm lenses are equipped with instant return automatic diaphragms and designated as Auto-Nikkors.”

To further simplify production and cut down on Nikon’s manufacturing costs, allowing them to present a broad lens lineup right upon release, the Zenza even moved the focusing helical to the camera body. That meant that the only direct control on the lens itself was for the aperture diaphragm.

As expected, the Nikkor lenses for the Zenza mount proved excellent in terms of optical performance and gave the camera very high marks in field tests. Other high points included the instant-return mirror, the auto-aperture stop-down with integrated depth-of-field review, and the smooth winding action of the large right-side knob.

The camera’s build quality and looks were also unanimously praised. Sculpted chrome flanks graced the Bronica’s body, evoking the aesthetics of 1950s American automobiles. All of the original Bronicas came in a unique light gray color scheme with a black stripe running down the middle. A large metal ‘Z’, for Zenza, graced the lid of the waist-level viewfinder.

Film loading was entirely automatic, and the camera used interchangeable backs with dark slides like many other professional medium-format cameras of the time. To prevent misfires, the shutter release locked itself when the darkslide was left inserted – another luxury the Bronica had over the Hasselblad.

Despite all these remarkable features, Bronica managed to market the Zenza at $489.50 at launch. That undercut Hasselblad quite severely, which sold its contemporary 500Cs – without the focal-plane high-speed shutter, without an instant-return mirror, and with much more expensive lenses-in-shutters by Carl Zeiss – in excess of $525.

Just to give you an idea, that made the Bronica’s initial price equivalent to just over $5,000, while the Hasselblad overshadowed it by more than 400 of today’s dollars. And that’s without a lens!

Competitive pricing aside, it’s fair to say the Zenza Bronica was still a very expensive camera, out of reach for the vast majority. Advertising material of the time presented it as “the Rolls-Royce of cameras” – no kidding!

Initial Refinements and Market Success

The original Zenza landed with a splash, not to great surprise considering all the hype surrounding it. The press loved it, and working photographers appreciated both its similarities and differences compared to the Hasselblad, both the original F-series it was based on and the C-series that had just launched.

To stay competitive, Bronica introduced a new, slightly revised model almost every year starting in 1959. The first was the Bronica D (for ‘Deluxe’), an updated version of the original with slightly different paint, improved materials for some internal mechanisms, and other minor aesthetic differences.

The Bronica D also introduced an easy-to-use mechanical facility for making double exposures, while further adding a self-timer. While simple, these were two key features that elevated the camera’s capabilities in the eyes of many working pros.

The next year, the D would be followed by the Bronica S. Sporting a tightened-up exterior design ready for the sixties, the Bronica S (‘Supreme’) was even heavier on the chrome than its predecessor. Opinions vary on the styling change, but nobody can deny it helped the Bronica stand out from the crowd even more than before.

For the sake of better quality control, some of the mechanically most challenging features of the original Zenza were toned down. The maximum shutter speed was lowered to 1/1000th, while the D’s self-timer was cut completely.

The Bronica S also started a trend of separating the original Zenza’s multi-functional controls. Whereas at first the large, right-hand knob was responsible for both shutter speed, film winding, and focus via the built-in helical, the S added a separate shutter speed control for the opposite hand to simplify the camera’s ergonomics.

Film winding was also now a lot faster, thanks to a heavy, chromed fold-out crank.

Including its very similar revisions and sub-models, which include the Bronica C, S2, and S2A, the S was by far the most common and most successful example of the original Bronica series, something that was likely sustained by its more attractive pricing compared to its exclusive predecessors.

Sales of the very last Bronica S variant ceased in 1974. By that time, its brand-new successor had already been in production for over two years.

Making the Electronic Bronica

By the release of the Bronica S2, research was already well underway on the mechanical Zenza’s planned successor. Yoshino was expecting a new, sleek replacement for the aging 500C from Hasselblad, and as with the launch of the original Zenza camera, he wanted to have something new and innovative ready to wow the public.

Instead of a mere face-lift, this new camera had to both supersede its older siblings in terms of performance and offer something truly fresh and new to the public.

The result of this endeavor was the Bronica EC, the first Electronically Controlled Bronica camera. Using an electronically-timed shutter meant that speeds were now much more accurate and required far less maintenance, while also giving the camera a chance to compete in a completely different segment of the market.

A new, sleeker look with more geometric motifs and subtler chrome detailing also set the EC apart while still maintaining the ‘Z’ family heritage.

The shutter speed control moved once again, this time to a small wheel just above and slightly in front of the winding knob. The new configuration was smartly laid out so that you could read all the various dials on the camera while looking straight down at it.

Besides the return of previously cut features, like double exposure and a self-timer, the EC also gained a few new tricks. These included a handy pocket on the film back for storing your dark slides. Swappable viewfinders now also contained their own, built-in light meters. A revision called the EC-TL would even allow the inclusion of a through-the-lens meter within the camera body, fed by the same batteries as the shutter.

The EC also offered handy interchangeable focusing screens for different shooting situations.

It’s likely that this last feature was implemented later in design as a deliberate jab at Hasselblad. The Swedish brand did release its successor to the 500C in 1970 as expected. However, the new 500C/M would do little to improve on the original’s specs save for the provision for add-in focus screens.

By choosing to go with the future – and solid-state electronic shutters were very much the future in the early 70s – Bronica managed to position itself as the more innovative, more professional brand as a counter to Hasselblad, whose simpler, all-mechanical design was starting to look like an anachronism as time went by.

Ramping Up Complexity and Performance

The EC series sold remarkably well throughout the seventies, making Bronica one of the biggest names in the medium-format scene.

In light of that, it might seem strange that none of the other big Japanese brands had plans to introduce a 6×6 square-format camera at that time.

In the end, this had to do with shifting tastes and demographics. Throughout the bulk of the Bronica’s lifespan, its target audience overlapped with that of Hasselblad: fashion photographers, portraitists, wedding shooters, and studio artists of all kinds.

It was these very same photographers who were now slowly switching over to other medium-format film aspects, most notably 6×7. Compared to square negatives, 6×7 offered an enticing increase in resolution and detail rendition, not to mention a so-called ‘perfect’ rectangular aspect ratio that could be enlarged to fit magazine covers without any cropping.

Bronica knew it had to save its humble 6×6 box from being usurped by these more modern, more expensive, and more heavy-duty rivals, but it didn’t yet have the capacity to make a direct challenger. Instead, Bronica chose to outflank the 6×7 SLRs with a sleeker, smaller, more compact alternative first.

The Bronica ETR

This would be the Bronica ETR, released in 1976. Designed for the unorthodox 6×4.5cm film format, the ETR could put 15 frames on one roll of 120 film. This made it much more economical than 6×7 SLRs, which generally couldn’t shoot more than 10 frames before reloading.

Bronica took Mamiya’s M645 camera, which came out just a year before the ETR, as a sign that the market was once again warming up to the idea of using ‘half-frame’ medium-format film. Ultimately, this proved to be a winning bet, as the 80s and 90s saw a significant uptick in sales for this aspect ratio.

As for the camera itself, the Bronica ETR was designed completely from scratch, sharing little with its predecessors apart from a few styling cues. The shutter was now of the central type, made by none other than Seiko. A state-of-the-art electronic unit, it ran from a solid 8 seconds up to 1/500th of a second. Like most, the ETR’s leaf shutters were all integrated into the lens housing.

Speaking of the lenses: sometime between the roll-out of the last Bronica ECs and the release of the ETR, the longtime partnership with Nikon met its end.

According to some contemporary rumors, this might have been a calculated exit made in mind with a potential medium-format SLR by Nikon themselves – though of course, such a camera never materialized.

Thankfully, Bronica had more than the necessary funds by the mid-70s to start thinking about designing and producing lenses of its own, which is exactly what it did starting with the ETR.

The ETR would end up becoming one of Bronica’s longest-running model lines, surviving all the way to the turn of the millennium in various guises. Later ETRS models added interchangeable metered prism heads, while revisions in the 90s introduced smoother, plastic-bodied styling that saved weight and added some more elaborate electronic features.

The ETR managed to outsell whatever competition it faced, such as the aforementioned Mamiya M645 series, principally based on its attractive price and large feature set. The first Mamiya, for instance, did not have an interchangeable film back, whereas the ETR had them from the very beginning.

The Square Returns

By the end of the 1970s, Bronica knew that sales from 6×4.5 cameras alone would not be enough to sustain its business. It also knew that most photographers still had an intrinsic association between the Bronica name and high-end, 6×6-format SLRs with a waist-level viewfinder.

Therefore, in early 1980, Bronica for the first time released an entirely new product without discontinuing its existing ETR models. The SQ (for ‘Square’) revived the look and form factor of the classic Zenzas, with all the electronic gadgetry and a toned-down, all-black, metal-and-plastic exterior that made it ready for the eighties.

Because of the end of the Nikon deal and the existing tooling and experience with the ETR, Bronica chose to offer the SQ with the same lineup of Zenzanon lenses and Seiko leaf shutters.

All the goodies you’d expect, both returns from classic Bronicas as well as nods to contemporary rivals, could be found on the SQ. From metered viewfinder heads to interchangeable focusing screens and add-on film backs for different formats, even including an adapter for Polaroid film, the SQ was a fully-featured system for the pros.

While sales of 6×6 camera gear were down overall compared to the 60s, the Bronica SQ was as good of a return to form as anyone could have asked for at the time and sold accordingly. Like the ETR, the SQ would end up seeing more than two decades’ worth of production in many iterative forms, becoming one of Bronica’s most enduring camera models.

Going Big With the Bronica GS

One final Bronica joined the stable in the eighties, the formidable GS. The brand’s weakness for chuckle-worthy puns never died, as the ‘Grand Shooting’ Bronica proves. Grand ended up being all too fitting of a label for this beast, Bronica’s first and only SLR to shoot the larger, highly coveted 6×7 format.

Released with a whole complement of lenses, viewfinders, focusing screens, film backs, and more in 1983, the GS was a bold move, to say the least.

In the eighties, medium-format shooting definitely seemed to gravitate towards 6×7, and Bronica realized that. What it perhaps didn’t realize is that simply scaling up an SQ would not be enough for many buyers.

By the year in which the GS was released, 6×7 medium-format cameras had become the exclusive high-end, whereas 6×6 and 6×4.5 were reserved for less expensive and less sophisticated machines for the most part.

When the GS-1 came out, its main competitor, the Mamiya RB and RZ series, carried a reputation for superior reliability and build quality that justified their much higher prices. At the same time, they included high-end features the Bronica lacked completely, such as revolving film backs and bellows focusing.

On the other hand, these extras made the Mamiya and others like it real beasts to use hand-held. The Bronica cut out a niche for itself by being the only major contemporary 6x7cm medium-format system marketed to pro photographers that was as lightweight as many 6×6 cameras.

By under-cutting the competition in terms of price, the GS also survived long enough to see the beginning of the 2000s with its stablemates. However, it did not allow the company to break into the highest echelon of medium-format photography as planned.

As a result, the GS played the role of the highly-engineered, but relatively neglected middle child during the period of the ‘three Bronicas’ from the early 80s to the 2000s.

The 90s: Signs of Trouble

Depending on whom you ask, the nineties were either the decade of smooth sailing for Bronica or the beginning of its downfall.

Case in point: all of its main three series, the ETR, SQ, and GS, survived past the end of the century in many iterations and improved variants. However, except for the later ETRS cameras, none of the Bronicas managed to come close to their sales peaks of the late 70s and early 80s during this decade.

The 90s would also be the only decade throughout Bronica’s history without any major new camera releases whatsoever. Tune-ups and revisions of the existing three branches were all that the public got to see.

It doesn’t take much to look at this outcome and surmise that Bronica was having trouble behind the scenes. Indeed, that was exactly what was going on.

Zenzaburo Yoshino passed away in 1988. With him, a lot of the visionary guidance and creative leadership that had defined the company’s camera design left, too. Its new management was not sure in which direction to turn.

Furthermore, the lack of breakout success of the expensive GS project had adversely affected Bronica’s bottom line. The SQ, intended as the bread-and-butter Bronica, sold much slower than the earlier Zenzas had, whereas it was surprisingly the cheapest ETR and ETRS that kept Bronica afloat, just barely.

Still, the cracks grew. With less and less of a budget to develop new lenses and significant features, let alone a new camera, Bronica lagged behind.

This was some grave timing, as much of the 90s would be the last time that film sales – especially medium-format – would really peak, and along with them film cameras, of course. The digital revolution was already on the horizon, and Bronica couldn’t even afford to think of its response to it.

Bronica Meets Tamron

In 1998, Bronica made public its formal acquisition by fellow Japanese camera company Tamron. Such mergers became increasingly common during the volatile turn-of-the-millennium period, as the sharp and sudden drop in 35mm film sales sent shockwaves throughout the industry.

Tamron initially had no great interest in the Bronica business apart from its tooling, factory space, and experience in high-end optics, which could be easily integrated into Tamron’s existing business strategies.

Despite that, Bronica’s new owners would greenlight one more camera to be built and designed entirely independently as a sort of swansong for the brand.

One Last Hurrah: The RF645

In the year 2000, Bronica released the RF645, a clean-sheet design that was both futuristic and retro at the same time.

Shooting 6×4.5cm exposures like the ETRS, the RF645 was a very compact, interchangeable-lens rangefinder camera with a fixed, solid one-piece body shell.

With state-of-the-art optics and metering, the RF645 was definitely at the top of the medium-format game in some sense for the time it was released in. On the other hand, the reliance on 120 film, not to mention the purely manual focus and lever winding with no motorized film transport, struck many reviewers as an odd choice.

Released during a time period when professional photographers couldn’t wait to jump on the digital camera hype train, the RF645 was commercially doomed from the start. That’s a shame, as it is an extremely interesting, unique, and highly versatile camera that was more portable than almost any modern medium-format system camera by any other manufacturer!

The End of Bronica

With sales long short of their targets, the RF645 was canceled in 2005. Not too long before that, all the remaining Bronica holdovers from before Tamron’s acquisition also ceased production.

There could have been an opportunity for a turnaround had Tamron given Bronica the opportunity to invest in digital sensor backs for the ETRS and SQ, for example. Such drop-in digital conversion backs were what ultimately saved Hasselblad, allowing it to survive into the 21st century under a partnership with Fujifilm.

However, no such Bronica digital back system ever appeared, likely because Tamron couldn’t afford to place a bet on such a risky maneuver.

While the story of Bronica formally ends there, in 2005, the brand’s legacy has never lost any of its importance. By helping to define the landscape of medium-format photography for a large part of the 20th century, Bronica has become one of the enduring names that will forever be associated with the medium.

The company’s extreme attention to detail, Zenzaburo Yushino’s aesthetic designs, and Bronica’s widely praised mechanical and optical craftsmanship also bled over into and influenced many of Tamron’s own designs through the 2000s and beyond.