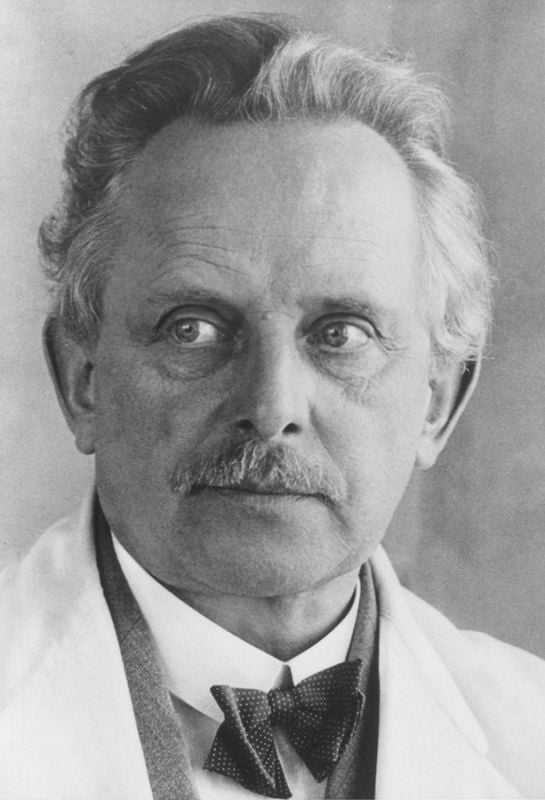

Oskar Barnack: The Father of 35mm Photography

![]()

Few technological achievements have changed not only their field but also the way our world works. The Gutenberg printing press, for example, revolutionized how we communicate, and in doing so changed the course of history. The advent of the 35mm film camera had a similar effect. Imagine a world without today’s cameras and the last century of photography. Impossible, thanks to Oskar Barnack.

Barnack’s prototype 35mm film camera became the first Leica camera, which quickly inspired an industry. Other 35mm cameras appeared. A new, innovative generation of photographers emerged. The world as we know it was unveiled.

Pre-35mm Photography

When Barnack was born in Germany in 1879, quality cameras resembled boxes the size of a milk crate. Lenses extended on a bellows, like an accordion, and the photographer often hid under a cloth to make an exposure. Glass plates coated with a light-sensitive emulsion served as “film,” and they proved incredibly heavy and fragile. The whole set-up seems ridiculous today, but pre-Barnack they were the best photographic method available.

Due to their cumbersome nature, glass plate cameras made it hard to photograph street scenes and distant landscapes. Photographers couldn’t just stop, press the shutter release and move on. Portraits looked, and were, staged.

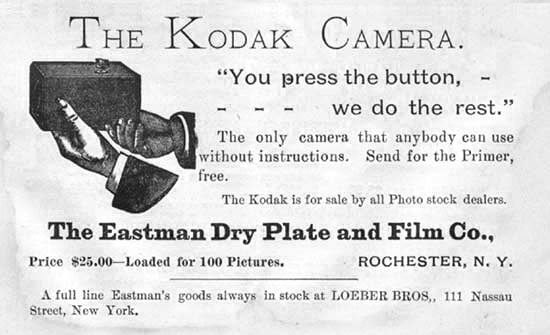

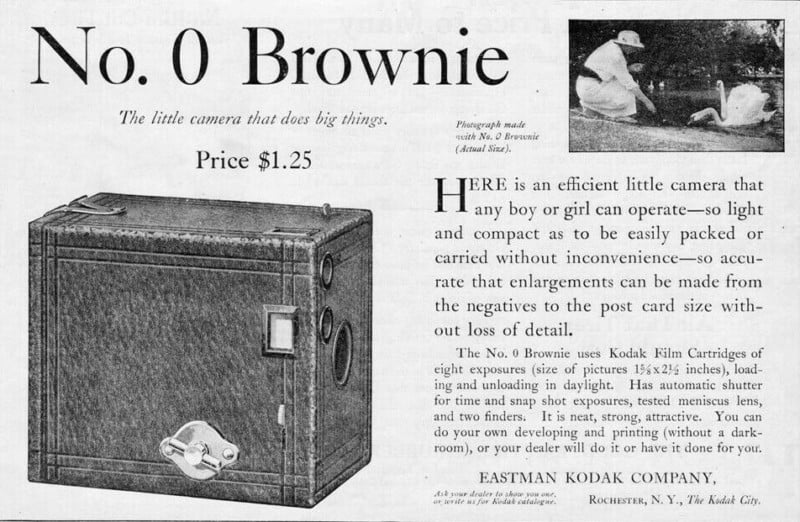

In Barnack’s early years, Kodak began pioneering consumer photography, launching the original Kodak camera in 1888 with flexible roll film, the Folding Pocket camera in 1897, and then the Brownie camera in 1900 to bring snapshot photography to the masses.

While these cameras brought the joy of photography to ordinary consumers through mass-market cameras, they left something to be desired in the area of quality, both of the camera build and of the resulting photos.

By the time Barnack began his career at the turn of the 20th century, a parallel genre had gathered popular attention. Cinema quickly pushed photography aside in the eyes of the masses, and this moving-picture application brought Barnack toward his photographic breakthrough.

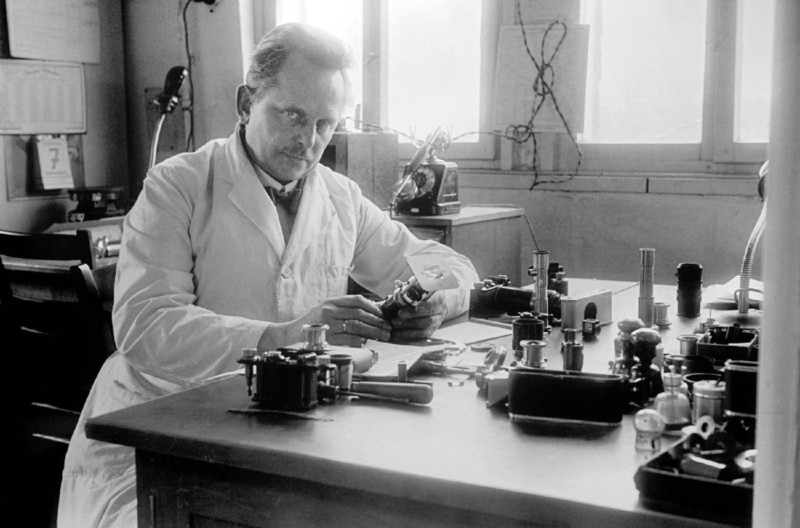

Barnack had already been experimenting with cinema film when he began working for Ernst Leitz II at the Leitz factory in Wetzlar, Germany. When not applying his mastery of precision mechanics to microscopes — Leitz, at that time, was the world’s largest manufacturer of microscopes, and also specialized in hunting riflescopes — Barnack built himself a cinema camera.

Unlike still photography cameras of the day, cinema cameras used film instead of glass. Thanks to this, Barnack’s cinema camera was smaller and lighter than a glass plate behemoth. While at Leitz, his mind kept working on side projects, which Ernst Leitz II noticed and encouraged. By 1913, Barnack had news to record in his workshop journal: “Lilliput camera for cine film completed.”

Barnack’s 35mm Film Camera

Lilliput refers to the diminutive people in Jonathan Swift’s book Gulliver’s Travels. Barnack’s prototype, soon named the Ur-Leica (ur- meaning primitive or earliest), was the first practical 35mm camera. Incomparably smaller and lighter than the contemporary glass plate camera, it was about the size of a modern Leica M camera, which still resembles the Ur-Leica in form.

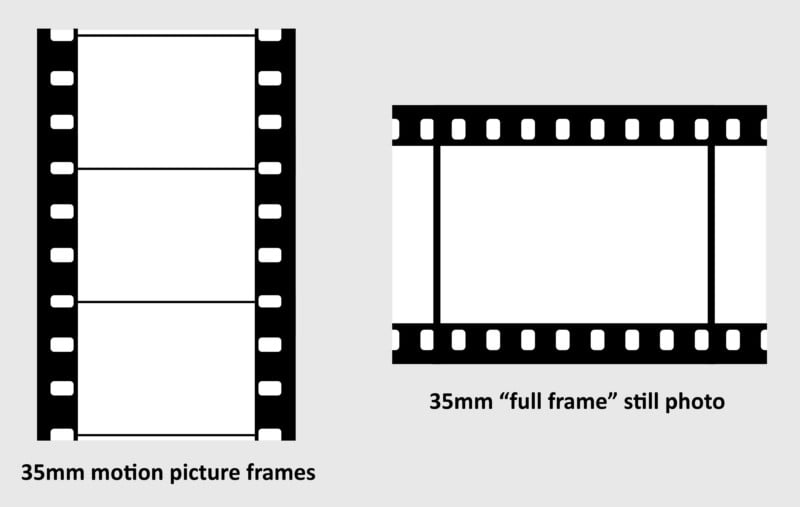

Barnack’s invention relied on cinema film, which was far more affordable than glass plates, but he turned the film horizontally and created the now-ubiquitous 24x36mm frame size.

Film allowed for more benefits than a departure from the heft and fragility of glass. With film, a photographer could now take multiple photos in a matter of seconds, rather than having to expose individual glass plates.

Enlargers allowed photographers to make large prints from the small yet finely-detailed negatives. Crucial to the quality of this process, however, was the premium lens. After World War I postponed the development of Barnack’s 35mm camera, Ernst Leitz II moved forward with the project. He commissioned a master lens designer, Max Berek, to fashion a lens specifically for the new camera. A 50mm lens proved to be optimal for the 24x36mm format. This lens would become the Leica Elmar.

In 1923, Leitz produced 23 Leica 0-Series cameras, which had a fixed 50mm f/3.5 lens. The following year, with Germany in the throes of a deep recession, Ernst Leitz II feared losing his employees for lack of work. Against the will of his advisors, Leitz decided to keep his factory going with the production of Barnack’s new camera. “My decision is final; we’ll take the risk,” Leitz declared.

Released at the Leipzig Spring Fair in 1925, the Leica I (also called the Leica A) began to impress photographers. The name Leica, a combination of the words Leitz Camera, soon earned its reputation for quality. It was robust, discreet, reliable, and easily carried. Amateurs began buying the camera, and professionals like Erich Salomon, Robert Capa, and Henri Cartier-Bresson soon caught on. By 1933, Leitz had sold 100,000 of its new Leica cameras, and the world had its first commercially successful 35mm camera.

While older photographers avoided Barnack’s invention, the younger crowd embraced it. Leica quickly became popular with the new generation of artists and photojournalists influenced by avant-garde styles like the Bauhaus movement.

Other companies soon copied the Leica, and the 35mm film camera market was born. Innovations like the single-lens reflex camera helped evolve Barnack’s creation further. But if we consider the photography that happened before and after the Ur-Leica, it’s clear that photography as we know it rests in large part on the merits of Barnack’s design.

Barnack’s Influence on Photography

Thanks to its minimal size and weight, the 35mm camera followed photographers into the streets, into warzones, into remote landscapes, and even into the air. The images that define the 20th century, including those made with medium-format cameras like a Hasselblad, owe their existence to Oskar Barnack’s innovative thinking.

Barnack made such a contribution to photography in part because he himself was a photographer. One impetus for the development of a compact, portable camera originated in Barnack’s own struggle with glass plate cameras.

Living in Wetzlar, Barnack liked to cover the city and its vicinity with his then-standard, massive camera. But he also suffered from a lung ailment that regularly sent him to sanatoriums. Lugging around a glass plate camera did no service to his weak lungs, so the prospect of a handheld camera pre-loaded with plenty of exposures appealed to Barnack on a personal, not just a mechanical, level.

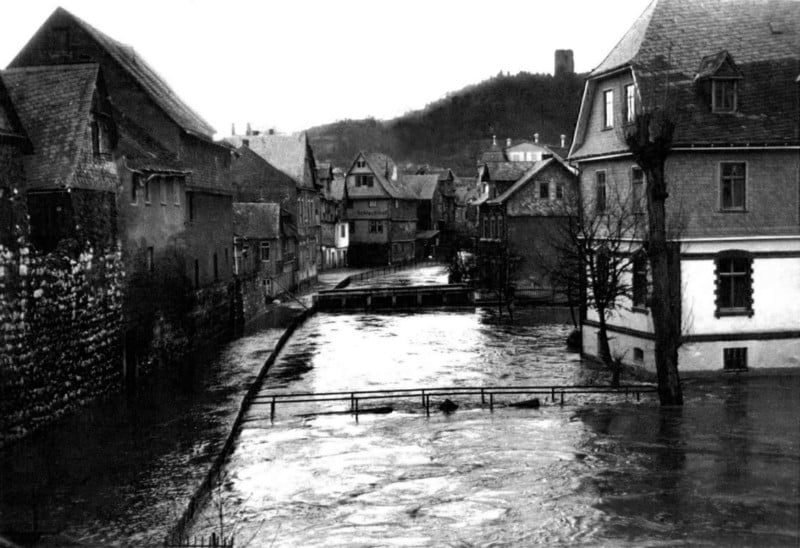

Barnack used his own Ur-Leica, which set a record in 2022 for the most expensive camera ever auctioned, to pursue his interests in street, portraiture, landscape and reportage photography. He recorded the 1920 floods in Wetzlar with his prototype Ur-Leica, a work now credited as the first reportage series made with a 35mm camera.

Such an easily transported and deployed camera permitted Barnack to document humanity’s relationship with nature. In honor of his achievements as a photographer and inventor, Leica created the Oskar Barnack Award in 1979, a century after Barnack’s birth. Entries for the award explore this human-nature question that Barnack himself pursued. In 1984, Oskar Barnack was inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum.

Just over half a century after Barnack’s untimely death in 1936, caused by pneumonia, photography turned away from film and into digital sensors. Yet Barnack’s influence remains, even though most photographers have not learned to recognize it.

Today’s DSLR and mirrorless cameras remain extremely portable and dependable. Compact cameras from companies like Fuji and Leica still show a direct lineage to the Ur-Leica. Full-frame digital sensors follow the same 24x36mm format of Barnack’s first camera. Even the latest iteration of a Leica film camera, the MP, is based on the legendary Leica M3, which itself began with the Leica I back in 1925.

It becomes impossible to consider photography as we know it without the visionary influence of Oskar Barnack. The dominance of the 35mm film camera, and all subsequent cameras it has inspired, proves that the format is the most applicable and enduring so far.

The last century of media and arts would not exist today without Barnack’s Lilliputian camera. Stories wouldn’t be shared with such wordless ease. The beauty of real life, in all of its glam and grit, would remain unseen. And very, very few of us would even bother with photography if it required hauling a glass plate camera from place to place. Even critics of Leica can acknowledge the fundamental contribution of Leitz engineer Oskar Barnack, the master mechanic who gave us modern photography.

Image credits: Header Ur Leica photo by Leica Microsystems.